People have wondered throughout the ages, are we fundamentally good or bad? Philosophers have debated for thousands of years about the basic state of the human nature. Psychology has uncovered some evidence that might help us to have a better understanding whether humans are intrinsically good or evil.

Pihlström – The Problem of Evil

Pihlström (2015, pp. 79-80) noted that the problem of evil has usually been approached from two different perspectives: from the traditional point of view of theology and philosophy of religion and from the point of view of secular ethics and politics supplemented by psychological and sociological explanation of evil acts. Pihlström also noted that it can be argued that these two rival discourses fail to recognise each other as adequate responses to the same problem of evil, which was interpreted differently throughout history.

Was the First Man Innately Good?

According to the book of Genesis (cited in Jones, 1968, pp. 5-6) the first man was innately good; after each day of creation, including the creation of Adam, God “saw that it was good” what he created. However, it can be argued that the creation is ongoing, as it was forbidden to Adam and Eve to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge, but their subsequent eating of it (first evil act of men) indicates that they have free will and ability to change things.

Theodicies Around Good and Evil

Leibniz (cited in Franklin, 2003, p. 97) questioned that if God exists, why God allows evil in the world. Also, he argued that there is a contradiction in asserting that God is perfectly powerful (omnipotent), as good and evil still exists. Therefore, Leibniz concluded that God does not exist. However, Pihlström (2015, pp. 77-99) noted that many theistic thinkers attempted to defend the free will theodicy and to challenge Leibniz’s theory. According to these theistic theorists, we cannot know God’s reasons for allowing evil. Nevertheless, Pihlström suggested that it is ethically disastrous to suggest that God might have “good reasons” to allow the world he created to be a place in which, for example, innocent children are led to gas chambers and allowing horrendous suffering. Rationalising theodicies make God himself an evil demon, so the reasons for the rejection of these theodicies are both ethical and theological. Pihlström suggested that the failure to develop a “realistic spirit” in this area of philosophical reflection is in itself an example of what Hannah Arendt (1963) called the “banality of evil”. The “banality of evil” is an expression that was invented to break with traditional and deceitful representations of evil as exceptional, profound and demonic and to highlight the insignificance (the banality) of the individuals, whose motives are also banal, ordinary and intrinsically non-criminal (Leibovici, 2007).

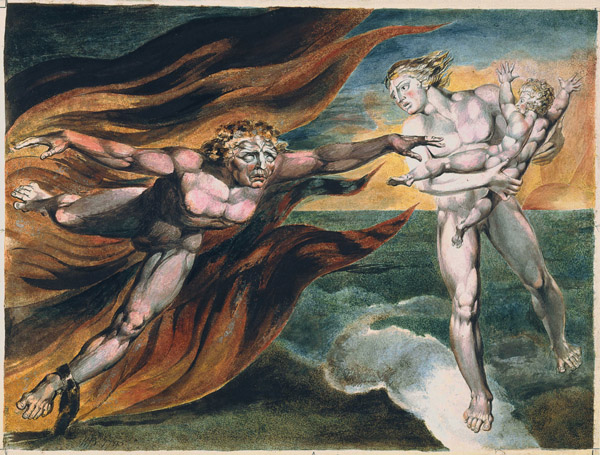

No Light Without Darkness

In contrast to Leibniz, Augustine had a different approach to the concept of evil. Augustine (cited in Outler, 1955) argued that originally everything is good as is the Creator of it. However, the good in created things can be diminished and augmented. Nonetheless, some remain of its original nature must remain as long as it exists at all; corruption cannot consume the good without also consuming the thing itself. Therefore, there is nothing to be called evil if there is nothing good. Nothing evil exists in itself, but only as an evil aspect of some actual entity; no shadow can exist without light. The good can exist without evil, but the evil cannot exist without good.

God Was Not Ignorant When Created the Evil

According to Augustine (cited in Rorty, 2001, pp. 37-53), the world was created and directed by divine love and benevolence. Man is endowed with the innate knowledge of the difference between right and wrong, but also with the dignity of free will. Man is capable of genuine and not programmed choice, however, his knowledge of good and evil is not always effective and accessible. This makes him frail and vulnerable. Since the world consists of nothing that is evil, selfish desires directed to things − food, sex, power − are genuinely good. But the self-oriented will perceives these things in a wrong way for the wrong reason. This can lead to seven sins, wickedness an vice. They are contrary to the supreme good nature of creation. The wickedness and vice can only flow where nature previously was not vitiated. The sinful soul makes the flesh corruptible as the mind becomes a slave of passion, which is not natural, but voluntary. However, Augustine emphasised the power of love, that can reorient the will, return the soul to proper harmony as guiding force toward the good. When God created the devil (which is good by God’s creation and wicked by his own will), God was not ignorant and foresaw the good which he would bring out of evil.

Evil is not Outside Ourselves

Similarly, according to James Allen (2009/1901, pp. 5-11), evil is not an abstract thing that is outside ourselves. It is there for a reason and it has a lesson for us. Patiently examining and rectifying our heart, the origin and nature of evil can be gradually understood, which will necessarily be followed by its complete eradication. All evil is corrective and remedial and is therefore not permanent. He also stated that the outside world that affects us is the mirror of our own experience. Everything that happens to us is part of ourselves. All the sins are rightly called “evil,” since they are the efforts of the soul to subvert, in its ignorance, the law that governs our mind. This leads to chaos and confusion within. Sooner or later sins will manifest in the outward circumstances as disease, failure, and misfortune, coupled with grief, pain, and despair. Whereas love, gentleness and good-will brings harmony and they become actualised in the form of health, peaceful surroundings and good fortune. By our own thoughts we make our life and the circumstances shape accordingly. Every soul attracts its own quality. Every soul is a complex combination of gathered experiences and thoughts, while our the body is a vehicle for its manifestation. We are the result of what we have thought. Allen does not deny that circumstances cannot affect us, however, he suggests that circumstances can only affect us in so far as we allow them to do so.

There are some overlaps between Allen’s view and the contemporary psychological approaches. For instance, Carr (2012, p. 326) suggested that psychologically minded people understand their problems as internal psychological processes, rather than blaming external factors. In addition, there are many studies that investigate how the environment (external factors) can affect individual behaviour, depending on their internal factors (e.g. vices and virtues). For example, social psychologists investigate how individuals behave in the presence of others (e.g. football violence). Besides, psychologists often investigate the risk factors that can cause antisocial behaviour, addiction or mental disorder. Also, studies about obedience to authority (e.g. Milgram’s study, 1963; Zimbardo; 1971) can be mentioned.

Evil Is Not Tangible

Although there are many scientific investigations about human characteristics, Morton (2004, cited in Javaid, 2015, p. 2) suggested that the “evil” is problematic to conceptualise and understand. Although in the Bible evil symbolises both moral and physical, the idea of evil is not tangible and it is difficult for society to understand. According to Dews (2007, p. 1) the idea of evil “hints at dark forces, at the obscure, unfathomable depths of human motivation”. However, in reality, there is a wide belief that the behaviour of individual beings can be accounted for in social and psychological terms (e.g. personal history, circumstances into which they are born), which can be altered.

Evil Is Part of the Human Heritage

According to Arandell (1987, p. 37), the self-fulfilling prophecy is an important phenomenon in recognising the qualities of “good” and “evil”. Both qualities can be fostered through social interactions. Parents can assign such characteristics to children and if the labelling is persistent, the child will take on that identity. Laub (1989, cited in Lemert, 1997, p. 8) investigated aspects of the collective human violence and concluded that individuals and groups have potentialities for good and evil. The direction they take is affected by different factors, such as economic hardships, nationality, ideology, cultural self-concepts and others. He highlights the idea that evil is not a scientific concept and its meaning has not been approved. However, the idea of evil is part of the human heritage.

The Problem of Evil

The idea of evil can be analysed from different perspectives. Both theodicies and social sciences have difficulties to understand the problem of evil. Perhaps the most convincing argument comes from Augustine, who concluded that evil cannot exist without good. He stated that naturally everything is good and the evil is the corruption of good, which can consequently exclude the idea that humans are intrinsically evil. Nevertheless, James Allen asserted that evil is not outside ourselves and it is corrective and not permanent. This approach can perhaps give a better understanding how God addressed the problem of evil when man was given the free will. However, this theory is still unable to answer the question, for example, why innocent children are led to gas chambers and allowing terrible suffering.

References

Allen, J. (2009). From poverty to power, or the realization of prosperity and peace. Charleston, SC: World Library Classics.

Arendell, T (1987) “A Sociological Perspective on sin and evil,” Quaker Religious Thought, 66)5, Digital Commons, [Online]. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/qrt/vol66/iss1/5 (Accessed: 27 April 2016).

Carr, A. (2012) Clinical Psychology: An Introduction. Hove: Routledge.

Dews, P. (2007) The Idea of Evil, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Franklin, J. (2003) “Leibniz’s solution to the problem of evil” in Think 2(5), The Royal Institute of Philosophy, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1477175600002670.

Javaid, A. (2015) “The sociology and social science of ‘evil’: Is the conception of pedophilia ‘evil’?” Philosophical Papers and Reviews, 6(1), DOI: 10.5897/PPR2014.0112.

Leibovici, M. (2007) “Banality of Evil” in Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, [Online]. Available at:

https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/banality-evil (Accessed: 30 April 2019).

Lemert, E. M. (1997) The Trouble With Evil: Social Control at the Edge of Morality, Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Outler, A. C. (1955). St. Augustine, Enchiridion: On Faith, Hope, and Love [Online] Available at: http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/augustine_enchiridion_02_trans.htm#C4 (Accessed 24 May 2016).

Pihlström , S. (2015) “The Problem of Evil and Pragmatic Recognition” in Value Inquiry Book Series (Academic Journal│Essay), 287, DOI: 10.1163/9789004301993_006.

Available at: https://brill.com/view/book/edcoll/9789004301993/B9789004301993-s006.xml

(Accessed: 30 April 2019).

Rorty, A. O. (2001)The Many Faces of Evil. London: Routledge.

The Jerusalem Bible (1968) Reader’s Edn., ed. by Alexander Jones, Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company.

Modified in 2019. See the Original here in PDF.

Facebook Comments