This essay investigates how female preferences for variations of male facial features may change across the menstrual cycle. This investigation is mainly limited to the preferences for variations of symmetry and masculinity in male faces across the menstrual cycle as most evolutionary psychology studies focus on these facial features. However, other facial features and factors are also analysed that may affect facial attractiveness.

Buss (2008, pp. 122-124) suggested that symmetry and masculinity in male faces are important for females as these traits provide health cues for potential partners. Investigations in 37 countries found that the desire for health in long-term mates is important for women. According to Little et al. (2007, p. 209) both male face symmetry and facial masculinity are cues to heritable fitness (‘good-genes’). They asserted that symmetry is a useful measure of the ability to cope with developmental stress, it can serve as an indicator of phenotypic and genotypic quality (e.g. the ability to resist diseases) and it can be related to reproductive success as well. Sexual dimorphism in human faces is a marker of genetic quality, yet there is no clear cut through the relationship between attractiveness and male facial masculinity.

Little et al. (2007, pp. 211-212) investigated preference for male face symmetry across the menstrual cycle. They compared attraction to symmetry in male and female faces in the late follicular phase of the menstrual cycle (high conceptual risk) and on the days between ovulation and the onset of menses (high progesterone level during luteal phase). The result indicated that preferences for symmetric faces were stronger in the late follicular phase (peak of fertility) than on days of the menstrual cycle with raised progesterone. They also found a cyclical preference shift for female faces. This may suggest that cyclic variation in symmetry preference is unlikely to reflect adaptations for increasing offspring health, but low-cost by-products of adaptive preferences for cues of genetic fitness in potential mates.

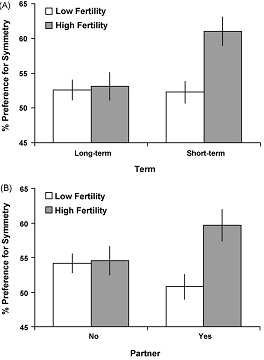

Little et al. (2007, pp. 212-214) also investigated facial symmetry and interaction among fertility, partnership and term. The result of this study found that women have different face preferences for short- and long-term mates according to their fertility. They preferred symmetrical faces only for short-term relationships, suggesting that symmetry is important when most likely to become pregnant (see Figure 1A). This finding is consistent with the idea that that shifting preferences across the menstrual cycle may facilitate the choice of high-quality partners at peak fertility for their potential to pass genetic quality onto offspring rather than provide paternal investment. Higher preference for male face symmetry was also seen when women were at higher fertility than when they were at lower fertility (see Figure 1B).

Figure 1: Symmetry preferences

According to (A) term (short and long-term) and fertility (high and low) and (B) partnership status (no partner and partner) and fertility (high and low)

(Source: Little et al. 2007)

Men with low fluctuating asymmetry (FA − random deviations from perfect symmetry) report higher numbers of sex partners and extra-pair copulation partners and shorter time elapsed until sex with a new partner (Gangestad, 2003, 2004 cited in Buss, 2005, p. 313). As changing preference for symmetry suggests that there is some cost to choosing symmetric partners otherwise they would likely be preferred under all circumstances. There might be heritable benefits to mating with males who have symmetrical faces, but there is a potential cost of lower paternal investment (Little et al. 2007, p. 213). Similar costs are apparent in masculine males. Highly masculinised male faces were perceived less warm, less honest and more dominant (Fink and Penton-Voak, 2002, p. 156).

Johnston et al. (2001, cited in Buss, 2008, pp. 123-131) developed a computer program that allows searching through hundreds of faces that vary in masculinity, femininity and other features. They discovered that women overall, regardless of their menstrual cycle, preferred more masculine-looking faces. They argued that masculine features are signs of good health as only males who are quite healthy can “afford” high levels of testosterone during development because it is compromising the human immune system. They found that although women, in general, are attracted to masculine faces, women who were at their peak of fertility preferred even more masculine faces than women who were in the phase of low probability of conception. Penton -Voak et al. (1999, cited in Buss, 2005, p. 355) came to a similar conclusion, in addition, they found that females at the peak of fertility prefer masculine face men as short-term sex partners only.

In order to control variables in related preference studies, researchers pay attention to select female participants who do not use hormonal contraceptives. In fact, Alvergne and Lummaa (2010, pp. 171-179) found that the use of oral contraceptive pills might decrease motivations for extra-pair sex at mid-cycle. This can lead to chosen men being of different phenotypes than those otherwise preferred (i.e. less masculine and symmetrical) which could have important long-term consequences for offspring. Also, the use of pills in a long-term context could influence the satisfaction and stability of long-term relationships and the ability of a woman to compete and retain her preferred mate, resulting from a potentially decreased attractiveness, as compared to normally cycling women.

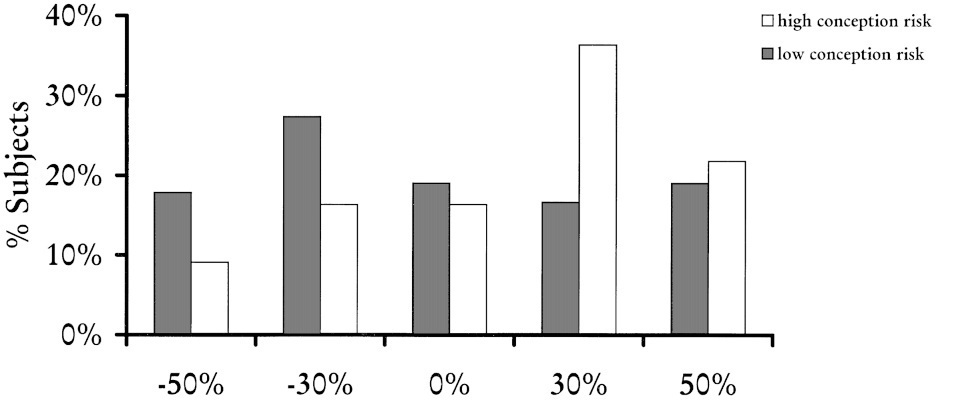

Penton -Voak and Perett (2000, pp. 39-48) also used a computer program to manipulate the masculinity or femininity of complex male faces by exaggerating or reducing the shape differences between female and male average faces. Five stimuli with varying levels of masculinity and femininity were presented in a national UK magazine, with a questionnaire asking respondents which of the five stimuli considered most attractive. Female subjects in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle (n=55) weresignificantly more likely to choose a masculine face than those in menses and luteal phases (n=84) − see Figure 2.

Figure 2: Masculinity preferences

Figure 2 shows the percentage of respondents selecting each face in high and low conception risk groups

(Source: Penton-Voak and Perett, 2000)

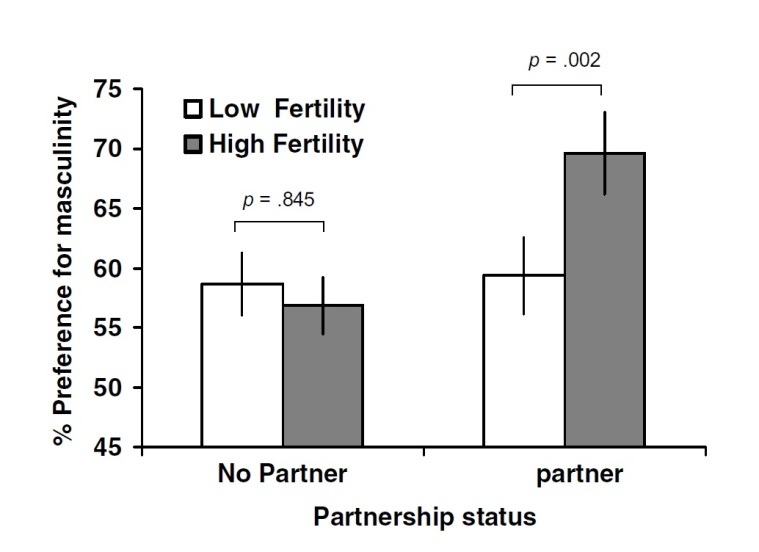

Little, Jones and DeBruine (2008, pp. 478-482) administered a study over the internet, with the difference from previous studies, that unmanipulated real male faces were used to address the reliability of findings that previously used manipulated masculine faces. Researchers came to the same conclusion that perceived masculinity in real male faces change across the menstrual cycle. Women preferred more masculine male faces when they were in the fertile phase of the menstrual cycle, however, this effect was seen only when women already had a partner (see Figure 3). This suggests that women’s preferences for perceived sexual dimorphism in real male faces follow a similar pattern as found for manipulated sexual dimorphism, indicating that real and manipulated masculinity in male faces generates similar results in preference.

Figure 3: Interaction between cycle phase and partner

Figure 3 shows preferences for facial masculinity by cycle phase noted as fertility (high/low) and partner (yes/no)

(Source: Little, Jones and DeBruine, 2008)

Harris (2011) questioned the reliability of two previous studies made by Penton-Voak et al. (1999) and Penton-Voak and Perrett (2000) about evolved mating strategy that women choose mates of maximum genetic quality when conception is likely. Harris (2011, pp. 669–681) stated that her study included a more complete evaluation of ovulatory status and a greater number (n=258) of target women than past researchers, yet her results did not indicate any greater preference for masculine faces when fertilization was likely. As a response to this study, Lisa DeBruine (2010, pp. 768-775) reviewed research evidences for cyclic shifts in mate preferences and discussed the weaknesses of Harris’s methods and her failure to replicate Penton-Voak and colleagues’ studies. Lisa DeBruine (2010) highlighted numerous studies that support increased attraction to masculine men around ovulation and uphold the idea that women are more likely to engage in extra-pair mating around ovulation, possibly to provide genetic benefits in offspring.

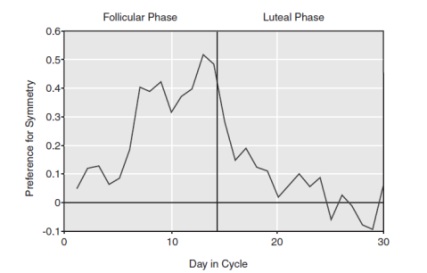

Another preference study made by Thornhill and Gangestad (1999, cited in Buss, 2008, pp. 131-132) found an interesting discovery related to women’s sense of smell. They asked men who varied in symmetry to wear the same T-shirt during two nights. After two days, T-shirts were collected and female participants were asked to smell them and rate each T-shirt how good or bad it smelled. Women judged the T-shirts worn by symmetrical men more pleasant smelling (or less unpleasant), but only if the women were in the ovulation phase of their menstruation cycle − see Figure 4. This study was confirmed by replicated studies done in different cultures by independent researchers (Rikowski and Grammer, 1999, cited in Buss, 2008, p. 132). Which chemical substances in men’s sweat are associated with symmetry is not completely known. It relates to Pheromones and sometimes Histocompatability (compatibility between the tissues of different individuals). Some theory and data suggest something androgen derived (Buss, 2005, pp. 354-355).

Figure 4: Women’s preference for scent

Figure 4 shows women’s preference for the scent of symmetrical men as a function of their day of the cycle

(Source: Buss, 2005)

According to Buss (2005, pp. 357-360) most findings related to preferences of male faces seem to be in line with extra-pair copulation theory (EPC). According to EPC, women are normally more attracted to men with facial cues of genetic benefits (symmetry and masculinity) when they are in the fertile phase of their cycle. Women on average report greater sexual attraction and interest in men other than primary partners when they are fertile than when they are non-fertile. Therefore, if their primary partner lacks indicators of genetic fitness, it is likely to show increased sexual attraction and interest in men other than primary partners when fertile. However, Buss (2005) suggests, there could be other alternative explanations for increased sexual attraction. For example, women may prefer short-term mates who can provide physical protection, although symmetrical men appear to invest less time and are less faithful to their partners, yet they may be better able to provide physical protection. Another possible explanation might be that women seek partners with high sperm quality in mid cycle, however, research findings in this area are controversial and alternative explanations fail to explain several details of the shifts-preferences for specific male features.

Fink and Penton-Voak (2002, pp. 154-158) summarised several attractiveness studies and they pointed out that evolved mechanisms for detecting and assessing cues for mate values are highly resistant to cultural modifications and people’s judgement of facial attractiveness is consistent with the theory of biologically based standards, although there are individual differences in attractiveness judgement. However, studies have indicated that some psychological factors influence preferences in a predictable way. For example, Johnston et al. (2001, cited in Fink and Penton-Voak, 2002, p. 156) compared psychological “masculinity” in females and found that females with low scores on psychological masculinity test showed a higher preference shift across the menstrual cycle, had lower self-esteem and greater preference for male facial dominance cues in potential short-term mates. They assumed that father-daughter bonding can increase female’s self-esteem and it can reduce sensitivity to male dominance cues, whereas lack of attachment can have an opposite effect.

Another study found that those females who consider themselves physically attractive showed a greater preference for masculinity and symmetry in long-term relationships (Little, Burt, Penton-Voak and Perrett, 2001, cited in Fink and Penton-Voak, 2002, pp. 156-157). Females who consider themselves physically attractive might be able to get different behaviour from masculine looking man than females who do not consider themselves attractive. It has been found that skin health is also positively correlated with male facial attractiveness (Jones et al., 2004 cited in Buss, 2005, p. 309). In addition, there are studies that highlight that there is a strong relationship between facial averageness and attractiveness (Little, Jones and DeBruine, 2015, pp. 1640-1645). Average faces are possibly attractive because the alignment of features is close to a population average. Recent studies have supported the link between averageness, heterozygosity (i.e. genetic diversity) and attractiveness. Facial expressions and facial personality traits may affect facial attraction too. Individual differences in preferences do not only depend on internal factors (e.g. hormonal state) but on the context and exposure (e.g. visual experience) as well.

Furthermore, as researchers focused only on the analysis of single features, this approach might be limited as the facial symmetry, hormone markers (i.e. masculine face) and averageness have interacting effects (Fink and Penton-Voak, 2002, p. 155). Each is signalling a different aspect of male quality. The mate choosers consider all facial and body features against one another to estimate the general condition of a potential partner.

A number of studies have shown that when women are in the fertile phase of their cycle they are normally more attracted to men with facial cues of genetic benefits and report greater sexual interest in men other than primary partners, especially if the primary partner lacks indicators of genetic fitness. However, the link between hormone markers, symmetry and attractiveness in male faces is complex. There are individual differences and there could be other social, cultural and psychological factors that might affect female preferences for male faces across the menstrual cycle. In order to make more reliable and valid investigations, perhaps all facial features and external factors should be considered.

See also: How Female Hair Influence Physical Attractiveness?

Bibliography

Alvergne, A., and Lummaa, V. (2010) “Does the contraceptive pill alter mate choice in humans?” Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 25 (3), pp. 171-179, DOI: 10.1016/ j.tree.2009.08.003

Buss, D. M. (2005) The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology. London: Wiley

Buss, D. M. (2008). Evolutionary Psychology: The New Science of the Mind. London: Pearson

DeBruine, L. (2010) ‘Evidence for Menstrual Cycle Shifts in Women’s Preferences for Masculinity: A Response to Harris (in press) “Menstrual Cycle and Facial Preferences Reconsidered”’ in Evolutionary Psychology, 8(4), pp. 768-775 [online] Available at: http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/comm/haselton/papers/downloads/DeBruine_et_al_2010_Response_to_Harris.pdf (Accessed 28 November 2015)

Fink, B. and Penton-Voak, I. S. (2002) ‘Evolutionary Psychology of Facial Attractiveness’ in Current Directions in. Psychological Science 11(5), pp. 154–158, DOI: 10.1111/1467-8721.00190

Harris, C. R. (2010) ‘Menstrual Cycle and Facial Preferences Reconsidered’ in Sex Roles, 64 (9), pp. 669-681, DOI: 10.1007/s11199-010-9772-8

Little, A, C., Jones, B. C. and DeBruine, L. M. (2015) ‘Facial attractiveness: evolutionary based research’ in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 366, pp. 1638-1659, DOI: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0404

Little, A. C., Jones, B. C. and DeBruine, L. M. (2008) ‘Preferences for variation in masculinity in real male faces change across the menstrual cycle: Women prefer more masculine faces when they are more fertile’ in Personality and Individual Differences, 45, pp. 478–482, DOI: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.05.024

Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., Burt, D. M. and Perrett, D. I. (2007) ‘Preferences for symmetry in faces change across the menstrual cycle’ in Biological Psychology, 76, pp. 209-216, DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.08.003

Penton-Voak, I. S., and Perrett, D. I. (2000). Female preference for male faces changes cyclically: Further evidence. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21(1), pp. 39-48, DOI: 10.1016/S1090-5138(99)00033-1

Facebook Comments